In the realm of high-fidelity audio, medical instrumentation, and precision aerospace sensors, the “quality of silence” is just as important as the quality of the signal. When a technician adjusts a volume knob on a microphone preamp or a sensitivity dial on an ECG monitor, they expect a seamless transition. However, beneath the surface of a standard component, a chaotic physical battle occurs. This is the phenomenon of “sliding noise” (also known as rotational noise or contact chatter)—a crackling interference that can ruin a recording or lead to a medical misdiagnosis.

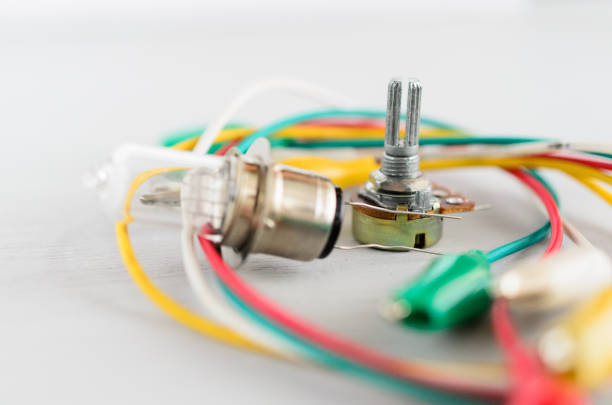

To achieve the “silent regulator” status, a high-end low-noise potentiometer must transcend basic electronic design. By utilizing precious metal composite brushes, specialized lubricants, and advanced electromagnetic shielding, engineers can suppress sliding noise to virtually inaudible levels. This article dives deep into the microscopic world of potentiometer architecture to reveal how material science and structural engineering preserve signal purity.

1. The Physics of the “Crackle”: Understanding Sliding Noise

Before we can suppress noise, we must understand its origin. Sliding noise is primarily a result of the dynamic interface between the moving wiper (brush) and the stationary resistive track.

The Contact Resistance Variation (CRV)

As the wiper moves across the resistive element, the contact is never perfectly smooth at a microscopic level. Small imperfections in the surface cause the contact resistance to fluctuate rapidly. This fluctuation creates tiny voltage spikes, which the system amplifies as an audible “crackle” or “hiss.”

Oxidation and Debris

In standard components, environmental exposure leads to the formation of oxide layers on the track. When the wiper scrapes across these oxides, it creates “intermittent contact,” further elevating the noise floor. In high-precision applications, even a few microvolts of noise can obscure the “background” of a weak signal, making suppression a critical engineering goal.

2. Material Innovation: Precious Metal Brushes and Resistive Tracks

The first line of defense against noise is the choice of contact materials. The interaction between the brush and the track must be stable, consistent, and chemically inert.

Precious Metal Composite Brushes

While entry-level potentiometers use simple carbon or base metal wipers, low-noise potentiometers employ multi-fingered brushes made from precious metal alloys (such as gold, silver, or palladium).

-

The Multi-Finger Design: By using multiple microscopic contact points (fingers) instead of one, the brush ensures that even if one finger encounters a microscopic speck of dust, the others maintain a solid electrical connection.

-

Chemical Stability: Gold and palladium do not oxidize. This ensures that the contact resistance remains constant over decades of use, preventing the “scratchy” sound common in aging consumer electronics.

Conductive Plastic Tracks

Traditionally, potentiometers used wire-wound or carbon film tracks. However, for ultra-low noise, conductive plastic is the gold standard.

-

Surface Smoothness: Conductive plastic tracks are essentially “mirror-smooth,” reducing mechanical vibration as the wiper slides.

-

Thermal Stability: These tracks offer superior heat dissipation, preventing the “thermal noise” that occurs when a component heats up during prolonged operation.

3. The “Liquid Buffer”: Specialized Lubricants for Signal Integrity

A critical but often overlooked component of the silent regulator is the damping grease or lubricant.

Reducing Mechanical Friction

High-performance lubricants act as a microscopic cushion between the brush and the track. They serve two purposes:

-

Damping: They provide a “silky” feel to the rotation, absorbing the micro-vibrations that would otherwise translate into electrical noise.

-

Oxidation Barrier: The lubricant creates an airtight seal over the contact point, preventing oxygen from reaching the track and forming resistive oxides.

Conductive vs. Non-Conductive Greases

Engineers must carefully select the viscosity and conductivity of the lubricant. A lubricant that is too thick may cause the wiper to “hydroplane” at high speeds, losing contact. Conversely, a lubricant with the wrong chemical makeup might attract dust. Advanced formulas used in precision potentiometers are designed to be self-cleaning, pushing debris away from the contact path as the shaft rotates.

4. Structural Shielding: Defeating the Invisible Enemy (EMI)

In high-sensitivity environments like medical labs or recording studios, the potentiometer acts like an antenna, picking up Electromagnetic Interference (EMI) from Wi-Fi signals, power lines, and motors.

Full Metal Shielding Enclosures

A “silent” potentiometer must be physically isolated from its environment.

-

The Faraday Cage Effect: By enclosing the resistive element in a grounded, all-metal housing (usually nickel-plated brass or zinc alloy), the component reflects external electromagnetic waves.

-

Internal Partitioning: Some ultra-high-end designs feature internal walls that separate the electrical terminals from the mechanical shaft, preventing external static electricity from “leaking” into the signal path.

Precision Grounding

A dedicated grounding terminal ensures that any parasitic capacitance or stray charge is immediately drained to the earth. This is vital for microphone preamps, where the signal level is so low that even a tiny amount of hum from a ground loop would be devastating.

5. Application Scenarios: Where Silence is Mandatory

5. Application Scenarios: Where Silence is Mandatory

The engineering efforts to suppress sliding noise reach their full potential in specific “mission-critical” applications.

-

Microphone Preamplification: When adjusting the “Gain” on a professional mic, any noise from the potentiometer is amplified by up to 60dB. A low-noise design is the only way to ensure a “black” background in high-resolution audio recordings.

-

Medical Diagnostic Equipment: In an EEG or ECG machine, the signals are measured in microvolts. A scratchy potentiometer could be mistaken for an irregular heartbeat or brain activity, making noise suppression a matter of patient safety.

-

Industrial Calibration: In laboratory-grade power supplies, the voltage must be adjusted with extreme granularity. Any “jump” in resistance due to sliding noise could cause a sudden spike in power, damaging sensitive prototypes.

6. Conclusion: The Art of the Invisible Adjustment

The ultimate goal of a potentiometer is to be invisible. It should change the signal without changing the character of the sound or the accuracy of the data. Through the sophisticated combination of precious metal metallurgy, conductive plastic technology, and hermetic shielding, the modern low-noise potentiometer achieves exactly that.

By eliminating the crackle of friction and the hum of interference, these silent regulators allow the true beauty of the signal to shine through. Whether you are capturing the delicate nuance of a violin or the vital rhythms of a human heart, the silence of the potentiometer is the foundation of your success. In the pursuit of signal purity, the best adjustment is the one you never hear.